The contours of the state of Texas line the inside of his thin arm in a clear black line. Luis is 23 years old, lanky, his flat dark hair sticks to his narrow head. He moves like a skater, loose pants, sneakers. “Why are you so proud to be a Texan?” I ask, and consider what it would be like to have a Bavaria or Berlin tattoo done. The tattoo seems elegant, beautiful even. We are standing in the lobby of a simple motel not far from the Mexican border. He pours coffee into a Styrofoam cup. In Texas, everything is bigger, gigantic even, the vastness is endless, the people are brave. When you go into a burger place here, he says, there’s this and that version of a hamburger. He counts them off, one after the other, a bunch of exotic names.

His mother’s ancestors were Lipan Apache from the south of Texas, he grew up in San Antonio, he never met his father who came from Mexico. “Our families have already been through everything. Everything is possible here. The people are more variegated than anywhere else. Texas is a separate world.”

Texas, the country where Europeans often only think of keywords such as slavery, native American wars, oil exploitation, capital punishment, weapons lobby, creationism, and militant anti-abortionists. A state on whose flag there used to be a snake baring its teeth and tongue. Above it: Don’t tread on me. Don’t regulate me, or I’ll get uncomfortable.

I traveled to Texas to see the whole picture, and to get to know the Texas that Luis is so proud of. I travel from the legendary artist town of Marfa in the southwest to Houston in the third biggest oil-producing region in the world, and from there to Austin, Boomtown of the USA.

To get to the end of the world in Marfa, one must drive through fields full of thousands of oil pumps that incessantly raise and lower themselves like divine hammers, in the sinuous rhythm of capital. No workers to be seen. Nobody. There are 1.1 million oil wells in the U.S., many of them only delivering 15 barrels a day – and almost exhausted. 3 of the 8 million barrels of crude oil that are extracted daily in the U.S. come from Texas. The monstrous oil refineries push their way into the picture, it smells like oil – only until the age of fracking dawns here, too.

In Marfa, the clouds knock on the windows from outside. I open for them, and step out into the glistening blue. In front of me lie the fields around the little artist town. Everything seems weightless, the heavens close, the ground far, proportions dissolve. “We are 1500 meters above sea level”, Jeff Elrod whispers behind me. Black jeans, black polo shirt, heavy boots. It feels like you’re on a board that’s being lifted towards the sky. The Texan artist converted a stall to an apartment and studio on the border of Marfa that stands in the middle of a vast empty plain like a space station. We climb atop a cattle gate to be able to see even further. It is as still as if all sounds had been sucked up into a vacuum. Alone in a space capsule, draped in expanse.

Jeff Elrod tears me roughly out of my dream. “Sometimes you can watch the clouds here in Marfa for an hour, watch how the storm comes closer, and then boom! I love watching storms.” He speaks fast, always keeping an eye on his counterpart. Exactly here, where we are now standing, people had fled over the green border of Mexico, across his property. They were sitting there having a picnic when he came home. “I turned around and drove away again”. He didn’t want to give them away, but also didn’t want to render himself liable to prosecution. When he came back, the border patrols had occupied his property. The heavily armed policeman gave him his card. On the back: “There is no hunting like the hunting of man.” Jeff Elrod waits for a second and then says: “It’s a quote from Hemingway”. And: “That’s the schizophrenia of Texas – Police, Hemingway, Manhunting.” The natural border to Mexico is considered one of the most dangerous and most-frequented migration-routes in the world. Every day, at least a thousand people without documents try to cross that border. Last year, a quarter of a million people were picked up and sent home. “I’m a convinced Texan”, says Elrod. “I hate Trump and am going to vote for Hillary.”

20 years ago, Jeff Elrod traveled through this place and saw Donald Judd’s concrete sculptures standing in a field. He stayed and discovered his painterly technique here, of all places. He was born in 1966 in Dallas, lived in California and Washington with his parents for a short time, then went back to Dallas for school and later for art school. “I grew up with video games”, he says, “with Pong by Atari. We would play all day. What eventually saved me was legendary Texan punk rock, the Butthole Surfers, they were ironic and wild. I went to 30 concerts. That was contemporary art. Split screen. High School Kids. And in the middle the band played with strippers and fireworks. Wonderful chaos. Conversations in my brain.” Jeff Elrod gets up. “That’s when I knew: I want to be a freak like that too, a weirdo.”

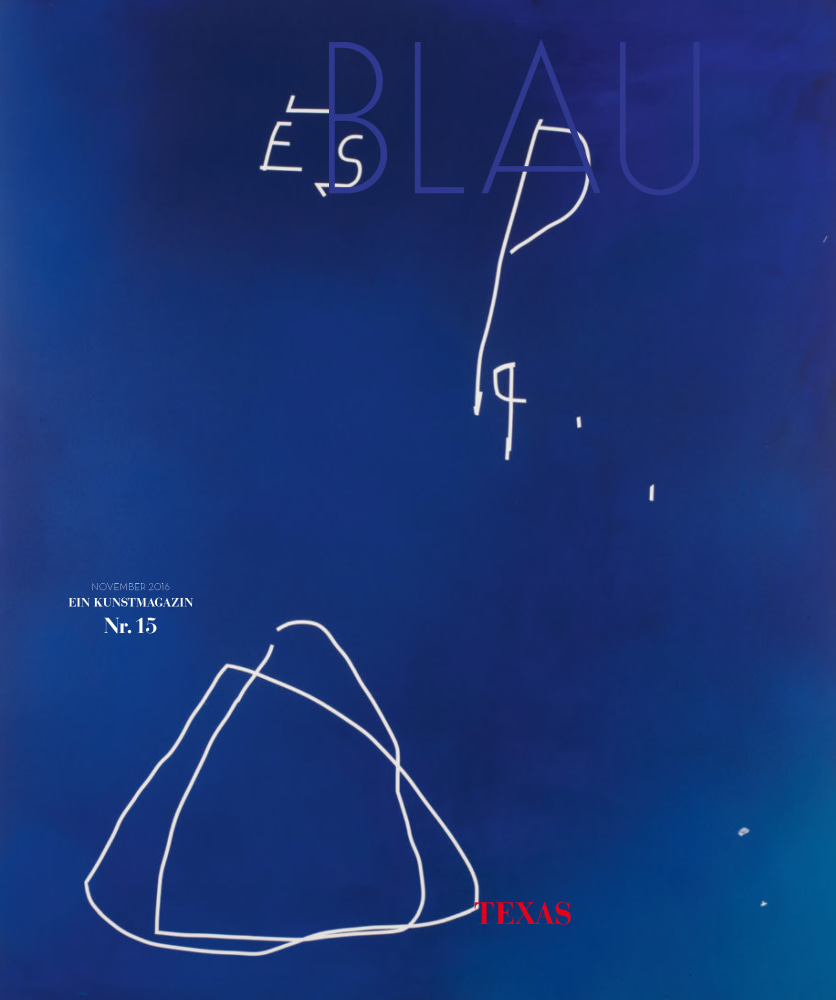

At 19 years old, Sigmar Polke got him off that trip and sent him right off on another one. He saw his matrix-prints and thought: That’s it. Elrod is a painter, his paintings originate from the graphics program Paint, he takes pictures of the screen, projects them onto the canvas and then copies them onto the canvas by hand. “The very first time I already felt that excitement again, like when I was a kid and played the computer.” Ever since, he has always looked for new techniques to save the digital aesthetic for reality. He tapes, paints, pulls off the tape again. In the past ten years, he has had exhibitions at MoMA PS1 and at the Whitney Museum in New York. The art critic, Roberta Smith, goes on a visual rollercoaster-ride with his paintings. You stick your head into an intoxicating cloud of color. The artist’s markings don’t allow you to completely take off. Weightlessness that gravity tugs on. A permanent state of things in Marfa. And in this moment, it seems evident why Texans lose sight of the rest of the world, why people walk around with T-shirts that say: “I wasn’t born in Texas, but I got here as fast as I could.”

Marfa is a pilgrimage site. The most important religion here is art. The minimalist Donald Judd moved here in the ‘70s, attracted other artists, and founded residency programs. Now there’s not just the Judd Foundation and the Chinati Foundation here. A grocery store sells fancy international groceries, Andy Warhol’s series The Last Supper is being shown in the gallery and shopping street. The long nights at the Lost Horse Saloon with the “one-eyed cowboy”, Ty Mitchell, a two-meter high giant with very narrow hips, are more authentic. He was featured in Halloween II from 1981, and his partner is Astrid Rosenfeld, a German writer who had unusual success with her debut novel holocaust story Adam’s Erbe. She’s already been here for three years now, she explains. Today she is helping at the bar. It is a place where people come together; artists, actors and theater directors from New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, but also Austin and Houston. A place where culture is more important than survival. On this parlor evening, everyone is drinking Lone-Star beer, is up in arms about the fact that a burger costs 18 dollars in Marfa, talking about the shooting of the Coen brothers’ movie No Country for Old Men in the desert, the artists Christopher Wool and Charline von Heyl, who also have a farm in Marfa, and the long Tequila night’s.

The place’s good days are over though, says Jeff Elrod. “Donald Judd wouldn’t move here anymore now. It’s become more of a good museum.” Meanwhile we are driving with his pickup truck through the few streets to his studio in town. Nobody stops, nobody gets out, dirty monstrous trucks turn around the corner, brake, drone away. Then pedestrians with jute bags appear. Art tourists, they are walking to Robert Irwin’s new light work. The locals stay in their cars.

He himself wants to take it down a notch. His success in the last years has wound him up a bit. He is important for Marfa, he is like a magnet, he attracts young artists. And he sends me off - to Jeremy DePrez, whose works he discovered a few years ago and with whom he has repeatedly shown in exhibitions since. Jeremy DePrez is currently on his way to becoming a star. Now, the New Yorker gallery Luhring Augustine is showing him in a group exhibition featuring shaped canvases, alongside Blinky Palermo and Frank Stella. And this coming spring he will have his first solo show in Germany at Max Hetzler in Berlin. Jeremy DePrez was born in Houston, where he lives and works. He doesn’t want to leave, either.